We’ve all seen the headlines over the last several weeks—I will paraphrase—Robinhood and its band of Merry Reddit Traders have come together to take down the greedy Hedge Fund Barons of Wall Street. While it makes for a compelling storyline and elicits many questions regarding how such things could happen, the reality of the plot is slightly less sensational, though there are some important implications to keep in mind. The story is really one of momentum, dislocation, and risk management, though again there are some key morals to this story.

The Power of Momentum

The practice of momentum trading is not new. There is long-term empirical data that suggests that momentum investing can be a profitable trade. The theory is the stocks that have done well in the past (usually a 3- or 12- month period) will continue to do well in the future. While many research articles have found this a reasonable trading strategy, they also tend to point to higher levels of risk and volatility—particularly at inflection points. In other words, momentum trading works… until it doesn’t and when it doesn’t it can move very quickly.

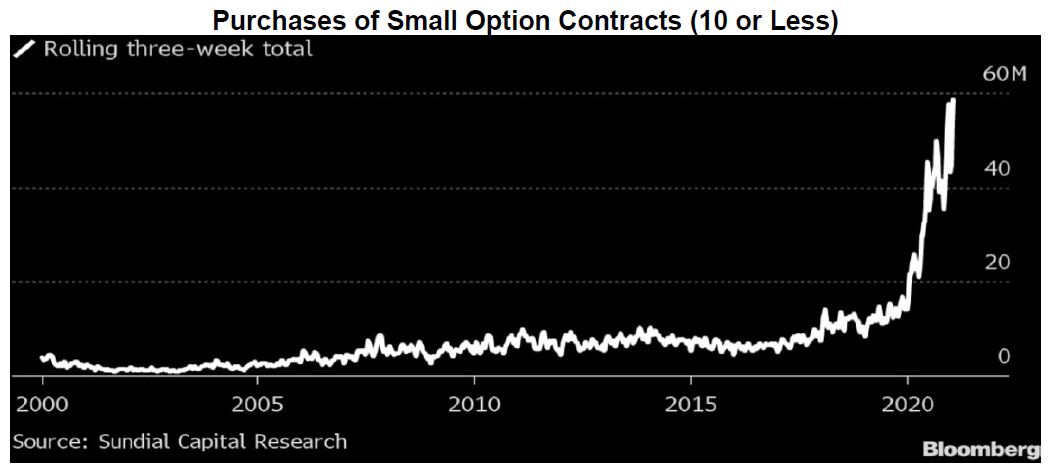

Recent phenomena are likely amplifying the momentum factor. With the growth of no-fee trading platforms and the democratization of trading, retail investing represents a higher percentage of total trading volume than it has in the past. The chart below from ABS Investment Management illustrates some of these changing dynamics, an example of which is the exponential growth of small option contracts.

The key question is whether this fundamentally changes the price discovery mechanism of equity markets. As we’ve seen over the last several weeks, the answer in the short run is yes. In the short-run, prices can become very disconnected from the fundamental value of a company. In the month of January alone, Gamestop traded between around $17 a share and just under $350 a share—implying that the value of the company was deemed to be somewhere between $1 billion and almost $24 billion. In the long-run, however, we continue to believe that the value of a company (and its stock) will follow and reflect its ability to generate earnings, which are either reinvested in growing the business or returned to shareholders.

Investment Implications

It seems January was part of our annual reminder as investors to remain focused on the long-run and to look past periods of significant market dislocations to identify the real factors at play. One clear example is going to be evaluating fund performance relative to their peers and benchmarks. The volatility of Gamestop is a perfect example. Gamestop represents less than a 0.2% position within the Russell 2000 Value Index—one of the indices that we use as a benchmark for small cap value investment managers. Typically, a position that small in size does not have a material impact on the index return for a month and therefore doesn’t register when evaluating the performance of a fund relative to its benchmark. In January, however, because Gamestop was up over 1700% in the month, it cost funds that did not own Gamestop several percentage points of returns relative to the index. Does this mean that the fund managers were wrong not to invest in Gamestop? We don’t believe so. It simply means that stock prices can become disconnected from reality. Further, the momentum trading phenomenon has the ability to either amplify the difference between price and reality and/or extend the time over which price and reality eventually converge. Ultimately this serves as a great reminder of the importance of thorough diligence and an in-depth understanding of the funds in which we invest.

Evaluating Risk in Long/Short Equity Funds

Long/Short Equity Funds (often lumped into the broad category of “Hedge Funds”) have a broader investing toolkit than typical funds. They can invest both long (investing expecting that the price of the stock will go up) and short (investing expecting the price of the stock to go down). Along those lines, two broadly accepted measures of risk in long/short funds are “gross exposure” and “net exposure”. Gross exposure is the sum of all of the stock positions in the fund—so the sum of all the “longs” and all the “shorts”. Net exposure is the difference between the total long positions and the total short positions. In practice, there is typically an offset between long and short positions—for example, if the broad market goes up, while the fund might lose money on the stocks it is short, it should make money on the stocks they are long. Therefore, the net exposure serves as a good indicator of the actual market exposure of a long/short equity fund. Typically, during periods of heightened volatility—usually triggered by some overall market event—long/short funds “de-risk” and do so by reducing both the long and the short exposure (and therefore their gross exposure). What this means in practice is that usually, when markets sell off, long/short funds lose money on their “longs” but make money on their “shorts”. So why are we going into such detail? One of the phenomena of the last month or so has been the fact that the de-risking has been due to a short squeeze—meaning the funds are losing money on their shorts. Add to that the selling pressure of having to sell out of some of their long positions to reduce their overall gross exposure, and you have losses on their shorts that are being compounded by losses on their longs.

Ultimately, the operative question is whether this “breaks” long/short investing? We don’t believe that it does. We found a quote by Michael Cembalest in a recent Atlantic article to be poignant, “the longer you’ve been around, the more you realize that something like this is less a massive break in the functioning of markets and more a reflection of the risks that were always there.” We don’t believe that the events of the last month reflect a new market paradigm. We still believe that in the long-run, fundamentals will drive investor returns. While the stock prices of companies like Gamestop, AMC and Blackberry have risen to levels that are seemingly devoid of fundamentals, the businesses remain challenged. The only key difference is that their stock prices have reached valuation levels that are very difficult to rationalize by most fundamental measures. In fact, these periods of extreme dislocation should in theory present opportunities for investors who controlled their risk and were able to maintain their positions. We believe that managers will learn from the circumstances and improve their risk management tools.

While the majority of investors were not actively involved in the euphoria and volatility of the last 30 days, we are not just un-invested spectators. The heightened volatility reverberated across a broad swathe of investments, so in a sense all investors were impacted—at least in the short run. That is the “price” to pay for being an investor in the public market. Our choice, however, is what we do when confronted with that noise. We continue to advocate for a fundamental and reasoned approach but appreciate that these periods can be unsettling. This only increases our resolve to ensure that our families understand and have confidence in what they are invested in and why we have conviction in these investments over the long run.

This report is the confidential work product of Matter Family Office. Unauthorized distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. The information in this report is deemed to be reliable but has not been independently verified. Some of the conclusions in this report are intended to be generalizations. The specific circumstances of an individual’s situation may require advice that is different from that reflected in this report. Furthermore, the advice reflected in this report is based on our opinion, and our opinion may change as new information becomes available. Nothing in this presentation should be construed as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. You should read the prospectus or offering memo before making any investment. You are solely responsible for any decision to invest in a private offering. The investment recommendations contained in this document may not prove to be profitable, and the actual performance of any investment may not be as favorable as the expectations that are expressed in this document. There is no guarantee that the past performance of any investment will continue in the future.